World Economic Situation And Prospects: April 2018 Briefing, No. 113

- Short-term prospects for the world economy continue to strengthen, but more efforts are needed to ensure the gains are widely shared

- Weak productivity growth and a lack of secure employment are constraining progress in many countries in Africa, Latin America and Western Asia

- Rising inequality in many countries pose a risk to medium-term growth prospects

English: PDF (214 kb)

Global issues

Stronger global economic growth, but risks are building

Over the last several months, short-term prospects for the world economy have continued to strengthen. This stems from a further uptick in the growth outlook for developed economies in 2018, on the strength of accelerating wage growth, broadly favourable investment conditions, and the short-term impact of a fiscal stimulus package in the United States. Many commodity-exporting countries will also benefit from the higher level of energy and metal commodity prices.

However, in parallel we have seen rising economic risks, including a rise in the probability of trade conflicts between major economies. The United States has announced the introduction of tariffs on specific imported goods, and other countries have reacted by drawing up plans for retaliatory measures. A move towards a more fragmented international trade landscape could reverse recent improvement in the global economy.

Will stronger global economic growth deliver improvements in living standards on a broad scale?

As emphasized in the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018, the improvement in macroeconomic conditions offers policymakers greater scope to address some of the deep-rooted barriers that continue to hamper more rapid progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. The rise in economic risks makes this challenge all the more imperative. These objectives include ensuring that the gains from stronger macroeconomic growth are widely shared, enabling progress towards targets such as reducing inequality, eradicating poverty and creating decent jobs for all.

Although average wage growth is accelerating in developed economies, in several countries there is evidence that these gains have accrued primarily to those at the higher end of the wage distribution. This rise in wage inequality follows a long-term trend, which is often quantified by considering measures such as the ratio of median to average wages. The median wage describes the wage exactly in the middle of the distribution, so that half of all wages are less than the median wage. In the member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), this median-to-average-wage ratio has declined by over 2 percentage points overall since 1995. This means that wages at the mid-point of the income distribution have fallen compared to the average wage, which in turn illustrates a more uneven distribution of wages.

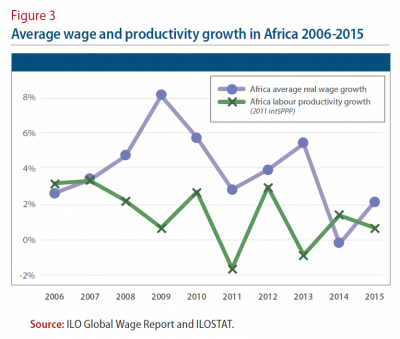

Rising wage inequality is one factor behind the widespread increase in income inequality observed in recent decades. The rise in income inequality in the United States over this period has been particularly pronounced, and is frequently cited as an important factor behind the rising appeal of more inward-looking policies. Inequality measures in many developing economy regions have also deteriorated (figure 1).

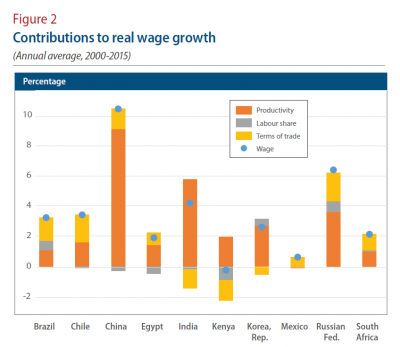

Another well-documented and related trend over the last few decades is the decline in the labour share of income, which is the share of national income paid to wage and salary earners. This has been associated with a widening gap between real wage growth and labour productivity growth. Through a simple identity relationship, real wage growth can be decomposed into associated changes in labour productivity growth, changes in the labour share of income, and changes in the “terms-of-trade” between producer and consumer goods.

At the firm level, a rise in labour productivity—which might reflect an increase in workforce skills or new technology that allows each employee to produce more goods in the same amount of time—brings added returns to the firm. These returns are then shared in some proportion among employee wages, payments for intermediate goods and other production costs, and returns to employers, including shareholders. A declining labour share of income indicates that a consistently smaller share of the available returns has accrued to employees. This is consistent with the observed rise in income inequality in developed economies. Shifts in the labour share may be driven by a number of factors, including changes in production structure and developments that may impact the relative bargaining strength of employees, such as the size of the available pool of labour, the potential for labour substitution through automation or outsourcing, job-specific skill requirements, unionization rates and labour market regulation.

A gap between real wage growth and productivity growth may also reflect shifts in the relative prices of consumer and producer goods. This captures the difference between the real wage from the perspective of employees, who use their income to purchase goods and services priced in domestic consumer prices, and the real wage from the perspective of employers, who pay wages out of their sales revenue. The dynamics of producer and consumer prices are often different, especially in non-diversified commodity exporters, where the consumption basket differs significantly from the production basket. During a commodity boom, producer prices rise faster than consumer prices. Real wages may rise at a faster rate than productivity if employees share in the associated windfall gains from higher export revenue. However, the opposite may occur when commodity prices fall.

Figure 2 shows a decomposition analysis of real wage growth between 2000 and 2015 of selected developing and transition countries (see footnote 3). In contrast to most developed economies, several of the large emerging economies have seen real wage growth outpace productivity growth over this period, including Brazil, Chile, China, the Russian Federation and South Africa. This predominantly reflects a rise in producer prices relative to consumer prices, driven by the high level of commodity prices over much of the sample period. Shifts in the labour share of income played a much smaller role.

The continued improvement in global macroeconomic conditions offers an opportunity to raise living standards on a broad scale. However, stronger economic growth in itself is not sufficient to ensure that these gains are widely shared. Building on the identity relationship underpinning the real wage decomposition reveals that there is scope to raise real wages even in the absence of strong productivity growth, through policy instruments that target the labour share of income. In an economy where wage inequality is high or rising, there may also be considerable scope to reduce the gap between the after-tax median wage and the average wage, through labour market policy instruments such as a minimum wage or restrictions on wage dispersion within firms, or through a more progressive system of taxes and benefits. While these measures often require politically challenging policy changes, tackling high and rising levels of inequality is a policy imperative, to enable progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Developed economies

Accelerating wage growth in developed economies

Wage trends present a mixed picture in Europe. In several of the larger economies in the region, including Germany and France, real wages are estimated to have increased at a moderate pace over the past few years, supported by solid or strengthening economic activity and moderate inflation rates. In other countries, however, real wages reflect more problematic conditions. Italy and the United Kingdom have registered negative or only slightly positive real wage growth, held back by weaker economic growth and hiring conditions, weak nominal wage trends or higher inflation rates. By contrast, various economies such as Poland and the Baltic States have seen more vigorous annual increases in real wages, reaching as high as 6 per cent, driven by a combination of tighter labour market conditions linked to outward migration and a catch-up effect with the rest of the European Union (EU). However, it should be noted that real wage growth in new EU members has persistently lagged behind the gains in productivity.

What is noticeable across the board is an accelerating trend in wage growth, in line with the marked fall in unemployment rates in the region. Wage growth is also accelerating in the United States, where average hourly earnings in the private sector are rising at their fastest rate in several years. The unexpected strength of wage growth is widely attributed to triggering the disruption of global stock markets in early February. In Japan, the Government recently introduced tax incentives to encourage companies to raise wages by at least 3 per cent in 2018, in efforts to spur consumer spending and raise inflation towards the central bank target of 2 per cent. However, many employers have been reluctant to meet this target.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Real wage growth in the Russian Federation rebounding

The economic recovery in the Russian Federation has allowed firms to gradually increase wages in 2017. This follows several years of volatile real wage patterns. Prior to the global financial crisis, real wages in the country were growing at double-digit rates, thanks to windfall oil revenues (consistent with the terms-of-trade gains discussed above). This was two to three times faster than the corresponding gains in labour productivity. Following a period of disruption, strong real wage growth resumed after the financial crisis, driven by rising wages in the public sector. The collapse in global oil prices in late-2014, coupled with international sanctions, contributed to a 9.5 per cent decline in real wages in 2015. The sharp disinflation in 2017, however, supported a return to positive growth in real wages, which exceeded 6 per cent in January 2018. Real disposable income, however, largely stagnated in 2017, as conservative budget policies have constrained social benefits and pensions.

Among other Commonwealth of Independent States energy exporters, real wages declined in 2016–2017 in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Among the energy importers, in Ukraine growth in real wages and real incomes reached 20 per cent in 2017, outpacing gains in labour productivity.

Developing economies

Africa: Labour productivity growth lagging the global average

In most African countries, income from self-employment generally accounts for a larger share of household income compared to developed countries. In 2017, only 30.8 per cent of the employed in Africa were wage and salaried workers, compared to the world average of 54.4 per cent and 86.1 per cent in high income countries (ILOSTAT). Nonetheless, the role of labour markets and wages in reducing poverty and inequality in the continent is important.

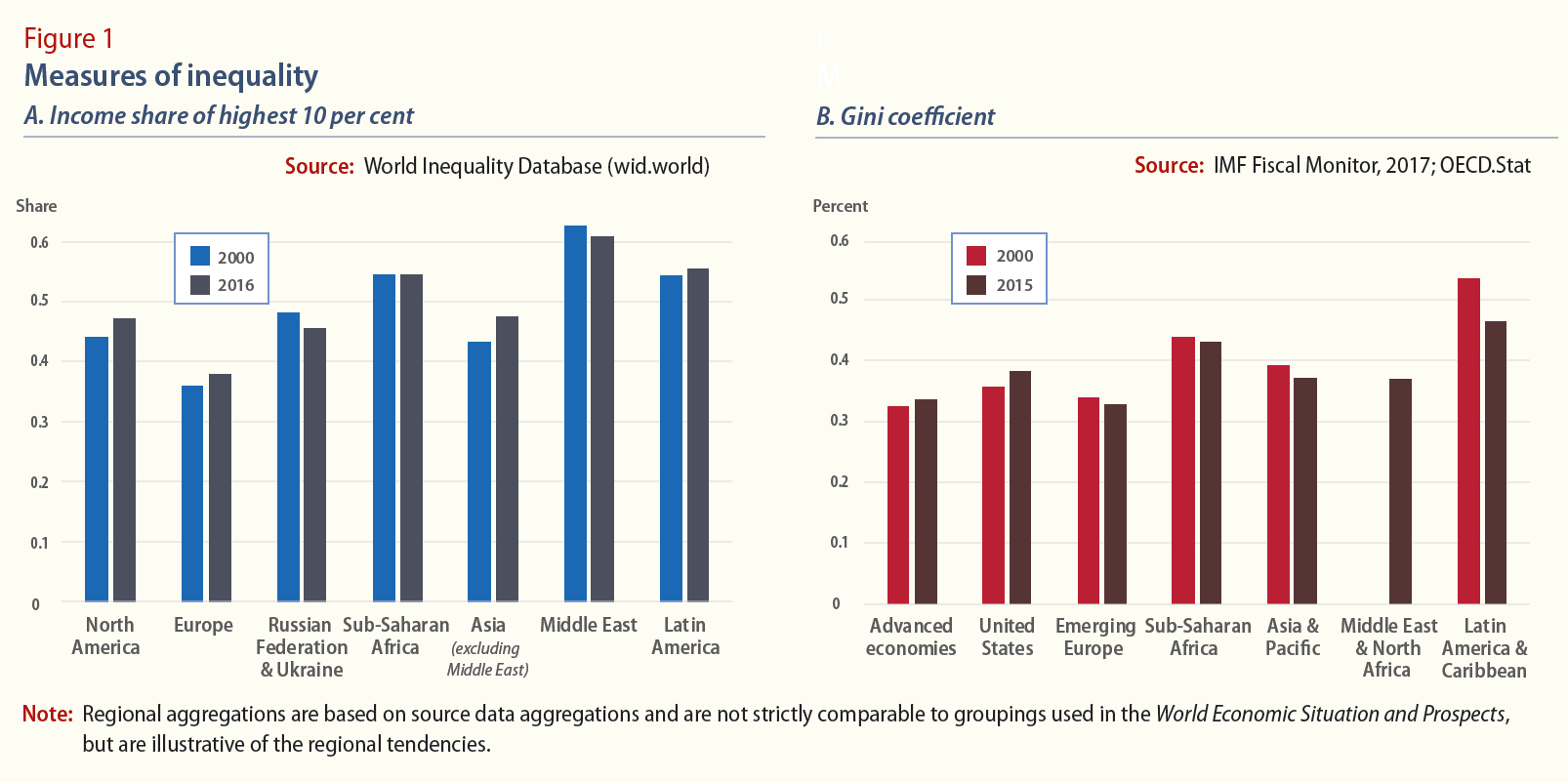

In 2015, Africa registered positive wage growth, following a contraction in real wages in the previous year, as commodity revenues declined amid rising inflation (see figure 3). In the long run, sustainable wage increases depend on increases in labour productivity. Labour productivity in the region has increased steadily since 1994, but has failed to keep pace with global labour productivity. In the decade leading up to the global financial crisis, Africa experienced a short period of catching-up, with labour productivity growing at a faster rate than the world average. However, convergence has ground to a halt in recent years, as productivity grew only marginally in 2015 and contracted in 2016–2017.

In 2015, Africa registered positive wage growth, following a contraction in real wages in the previous year, as commodity revenues declined amid rising inflation (see figure 3). In the long run, sustainable wage increases depend on increases in labour productivity. Labour productivity in the region has increased steadily since 1994, but has failed to keep pace with global labour productivity. In the decade leading up to the global financial crisis, Africa experienced a short period of catching-up, with labour productivity growing at a faster rate than the world average. However, convergence has ground to a halt in recent years, as productivity grew only marginally in 2015 and contracted in 2016–2017.

In recent years, wages have increased faster than labour productivity. This has manifested itself in an increasing labour share of income since 2007 in fourteen countries, reversing the steady decline in labour share observed between the mid-1980s and 2007.

The rising labour share of income in Africa since 2007 has been associated with only limited progress in reducing income inequality. In South Africa, wage inequality decreased from 2000 but it remains very high. The highest-paid 10 per cent receive on average 49.2 per cent of the total wages paid to all employees and the top 1 per cent obtain 20.2 per cent. The lowest-paid 50 per cent receive just 11.9 per cent of all wages paid out. Gender income inequality is also prevalent. For example, in the United Republic of Tanzania, 42.3 per cent of female employees receive an hourly wage worth less than two-thirds of the median.

East Asia: Rising income inequality clouding China’s sustainable growth prospects

Buoyed by resilient domestic demand, the Chinese economy is projected to continue expanding at a solid pace of above 6 per cent in 2018 and 2019. However, this robust short-term growth outlook masks several structural issues that are posing a challenge for China in achieving more balanced and sustainable growth. Notably, income inequality has been on an upward trend, amid rising urban and rural income disparity. Recent official data showed that China’s Gini coefficient increased from 46.2 per cent in 2015 to 46.7 per cent in 2017.

Against this backdrop, the Chinese authorities are intensifying policy measures to tackle inequality and promote more inclusive growth. In 2017, 20 regions increased their minimum wage rates, as compared to only 9 regions in the previous year. Pension reforms will also be a key focus, which includes the creation of a centralized system for employees’ basic pension funds. Furthermore, the Government’s strategy to attract more investment into the high technology sectors is likely to lead to productivity and employment gains, contributing to higher real wage growth.

South Asia: Inequality in India is on the rise

The Indian economy has been expanding at a robust pace over the past two decades, with annual GDP growth averaging 7.1 per cent between 1990 and 2016. This favourable growth performance has in turn contributed to a visible reduction in poverty rates. However, this positive picture is marred by growing evidence of high, and rising, levels of inequality, amid increasing disparities between urban and rural areas, as well as within urban areas. Recent estimates show that the Gini coefficient on disposable income in India has risen from about 45.0 in 1990 to close to 51.0 in 2013. Meanwhile, combining tax and survey data and national accounts, Chancel and Piketty showed that the share of national income attributed to the top 1 per cent of earners has risen steadily from 6.2 per cent in 1984 to a record-high of 22.0 per cent in 2014. The most recent estimate also suggests that the top 10 per cent of earners received about 55 per cent of national income, more than 20 percentage points higher than in the mid-1980s, when liberalization and deregulation reforms were initially implemented. In addition, the share of national income held by the bottom 50 per cent has fallen sharply from 24 per cent in 1983 to less than 15 per cent in recent years. This growing polarization of living standards presents a crucial development challenge for India. Rising inequality can slow poverty reduction and weaken the pace and sustainability of economic growth. Against this backdrop, the Government should take proactive action in promoting a more inclusive growth trajectory that is in line with “leaving no one behind” and the 2030 Agenda.

Western Asia: Persistently weak wage and productivity growth a major challenge for oil producers

Since 2000, the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have grown at a moderate pace, with real GDP expanding at an average rate of 4.7 per cent per annum. However, during this period, wages and labour productivity developments have deteriorated. From 2000 to 2015, labour productivity is estimated to have contracted at an average annual rate of 1.5 per cent in Bahrain, 1.1 per cent in Kuwait, 1.2 per cent in Qatar and 0.8 per cent in Saudi Arabia. Real wages over this period are estimated to have contracted at an average annual rate of 3.9 per cent in Bahrain, 2.1 per cent in Qatar and 0.1 per cent in Saudi Arabia. Kuwait is estimated to mark weak but positive average wage growth by 0.7 per cent annually over the same period. In order to maintain the recent pace of economic growth, GCC economies have relied upon a significant increase in the labour force. The additional labour supply primarily reflects an influx of foreign workers. The low wage level offered to foreign labour has suppressed the average wage growth and widened the wage inequalities between foreign and national workers. Recent economic reform measures in GCC countries target productivity-led economic diversification, which can be challenging as it will entail a transformation towards economies that are less dependent on foreign labour.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Slow productivity growth restraining wage gains

Following three consecutive years of contraction, GDP per capita in Latin America and the Caribbean is estimated to have stagnated in 2017. The economic downturn underscored the region’s continuing dependence on external factors, most notably commodity prices. It also brought to the fore widespread institutional deficiencies and macroeconomic weaknesses, which continue to hinder productivity growth in the region. Since 2000, about three quarters of the region’s GDP growth has come from rising labour inputs rather than from increased productivity—a share that is larger than in any other region in the world. During this period, labour productivity growth averaged only 0.7 per cent per annum, far below the developing country average of almost 4 per cent. Estimates of total factor productivity, which measures an economy’s efficiency in transforming capital and labour into output, have declined in eight of the past ten years. According to a recent World Bank study, the region’s weak productivity performance in recent decades is largely due to resource misallocation, with slow technology adoption playing a lesser role. In many Latin American countries, ongoing structural shifts have catalysed the movement of workers to lower-productivity jobs in the service sector, resulting in lower value-added per worker. Slow productivity growth, in turn, has limited wage gains in much of the region. Based on ILO data, average real monthly earnings grew at an average annual rate of just 0.9 per cent between 2000 and 2015.

1 Schwellnus, C., A. Kappeler and P.A. Pionnier (2017), “Decoupling of wages from productivity: Macro-level facts”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1373, Paris.

2 See, for example, Karabarbounis, L. and B. Neiman (2014) “The Global Decline of the Labor Share,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 129, No. 1, pp. 61-103.

3 See equation (1) in Uguccioni, J. and A. Sharpe (2016), “Decomposing the productivity-wage nexus in selected OECD countries, 1986-2013”, CSLS Research Report 2016-16, November. The decomposition in figure 2 is based on a simplified version of this identity, which does not imply causal relationships.

4 Chancel, L., and T. Piketty (2017), “Indian income inequality, 1922-2014: From British Raj to Billionaire Raj?”, WID.world Working Paper Series, No. 2017/11, available from http://wid.world/document/chancelpiketty2017widworld/

5 Based on internal estimates by the Global Economic Monitoring Unit of the Development Policy and Analysis Division, UN/DESA.

6 Araujo, J. T., E. Vostroknutova, K. M. Wacker, and M. Clavijo, eds. (2016), “Understanding the income and efficiency gap in Latin America and the Caribbean”, World Bank Group, Washington, D.C., available from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23960/9781464804502.pdf

Follow Us