The Emerging Threat of Upper Atmosphere Congestion on Earth-Observation Satellites and Climate Intelligence

Earth-observation satellites have become indispensable for strategic intelligence in climate change, disaster response, agricultural planning, and environmental monitoring. A developing weak signal, however, suggests that the rapid increase of space congestion in low Earth orbit (LEO) and the risk of collision with space debris could severely disrupt this vital capability in the decade ahead. This challenge goes beyond technical hazards—it threatens decision-making frameworks across multiple industries relying on near-real-time, accurate environmental data.

Introduction

Earth-observation satellites capture critical data that underpin climate science and facilitate the monitoring of environmental changes globally. Yet, the growing congestion in low Earth orbit, driven by accelerating satellite launches and accumulation of space debris, poses a mounting risk to these missions. This weak signal of upper atmosphere congestion could emerge as a disruptive trend, affecting industries that depend on satellite-borne data to understand and respond to climate change, natural disasters, and geopolitical shifts.

What’s Changing?

International space agencies and private companies have launched increasing numbers of satellites into low Earth orbit to capitalize on enhanced data collection and communications capabilities. This surge, however, is rapidly congesting orbits traditionally reserved for Earth observation missions. The consequence is an elevated risk of physical collisions and a potential loss of satellite assets essential for monitoring climate risks.

One reputable source highlights ongoing redesigns of earth-observation missions that explicitly aim to mitigate collision risks from space junk, confirming the recognition of this threat at the operational level (E&T The Institution of Engineering and Technology).

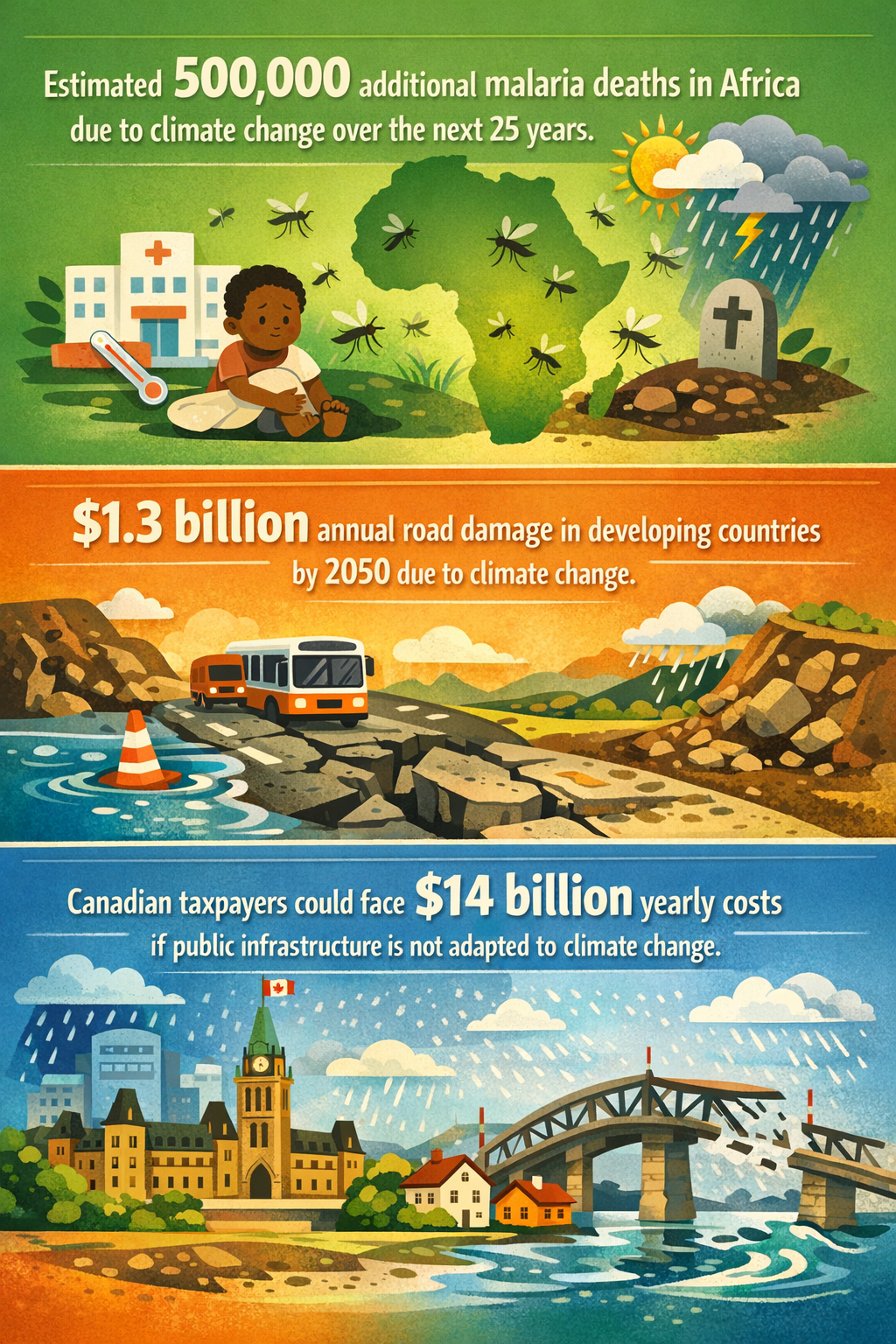

Simultaneously, climate change pressures intensify demands for satellite data. For example, satellite feeds inform assessments of warming effects in vulnerable regions such as Africa’s malaria-prone zones, where climate impacts could add over 500,000 deaths by 2050 (Ecofin Agency). Satellites also track ice melt trends in the Arctic with geopolitical implications should ice-free conditions materialize in September by century's end (Impakter).

The fragility of such systems contrasts with growing regulatory fragmentation related to climate risk disclosures by multinational firms, which depend on robust environmental data to quantify and reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Conference Board). Without reliable satellite observations, companies and governments could face uncertainties in reporting and managing climate risks accurately.

Furthermore, climate adaptation infrastructure projects face financial pressure globally—for example, Canada may spend $14 billion annually if trillions in infrastructure fail to adapt to climate shifts (CityNews Montreal). Such investments rely on predictive environmental analytics from satellites, which could degrade if upper atmospheric risks materialize.

Why is this Important?

The potential degradation of Earth-observation satellite capabilities due to space congestion directly threatens the accuracy and availability of environmental data essential for a wide range of sectors:

- Climate science and epidemiology: Tracking climate-driven disease vectors like malaria and heat-related mortality requires continuous environmental monitoring.

- Infrastructure planning and adaptation: Costly public projects hinge on reliable climate projections, increasingly reliant on satellite inputs.

- Corporate climate risk management: Uncertainty or gaps in data could hamper transparency and compliance as firms respond to fragmented regulatory demands for GHG disclosures.

- Geopolitical strategy: Governments monitor shifts in Arctic ice coverage and other environmental indicators that influence territorial claims and resource access.

Failure to secure Earth-observation assets may increase operational risks across these domains, resulting in delayed or inaccurate decision-making prone to “unknown unknowns” related to environmental shifts. The challenge is compounded by a potential feedback loop: more satellites launched to compensate for lost capacity may worsen orbital congestion further, escalating collision risks.

Implications

Satellite operators, governments, and regulatory bodies must proactively address upper atmosphere congestion as a strategic threat to climate intelligence and risk systems. Potential implications and responses include:

- Policy and regulatory coordination: International collaboration might emerge to harmonize orbital space management, including limits on satellite numbers, mandatory debris removal, and sharing of space situational awareness data.

- Technology innovation: Development of collision avoidance systems, satellite designs resilient to debris impact, and efficient debris removal technologies could become critical industry segments.

- Data diversification and redundancy: Organizations may invest in alternative means of environmental data acquisition, such as aerial drones, ground sensors, or in situ measurements, hedging against satellite disruption.

- Revised risk assessments: Businesses and governments may need to incorporate satellite congestion risk into their climate risk disclosures and infrastructure planning, potentially affecting capital allocation and insurance markets.

- Impact on emerging economies: Regions like Africa, which face increasing climate-health risks and lack extensive ground infrastructure, may become disproportionately vulnerable if satellite services degrade.

Failing to recognize space congestion as a climate intelligence risk could severely hinder efforts to understand and manage the pace of climate change and its cascading socio-economic effects.

Questions

- How can international space governance evolve to balance the need for data access with orbital sustainability?

- What investments in satellite technology and debris mitigation should governments and private players prioritize to secure climate intelligence?

- How will disruptions in satellite data affect sectors relying on climate projections, and what contingency plans are realistic?

- Could decentralized or alternative environmental monitoring systems emerge as critical supplements to satellite data?

- What role will transparent climate risk disclosures play in highlighting the indirect impacts of space congestion?

Keywords

Earth-Observation Satellites; Space Debris; Climate Intelligence; Orbital Congestion; Climate Risk Disclosure; Climate Adaptation

Bibliography

- Earth-observation missions redesigned to cut risk of space junk strikes. E&T The Institution of Engineering and Technology.

- Climate change could drive up malaria deaths and costs in Africa by 2050. Ecofin Agency.

- Climate Risk Disclosure: Regulatory Efforts. The Conference Board.

- How Climate Change is Reshaping Arctic Geopolitics. Impakter.

- Canadian taxpayers will pay $14 billion annually without climate-adapted infrastructure. CityNews Montreal.